? Barebones React/Sass/Express/TypeScript Boilerplate

? Purpose

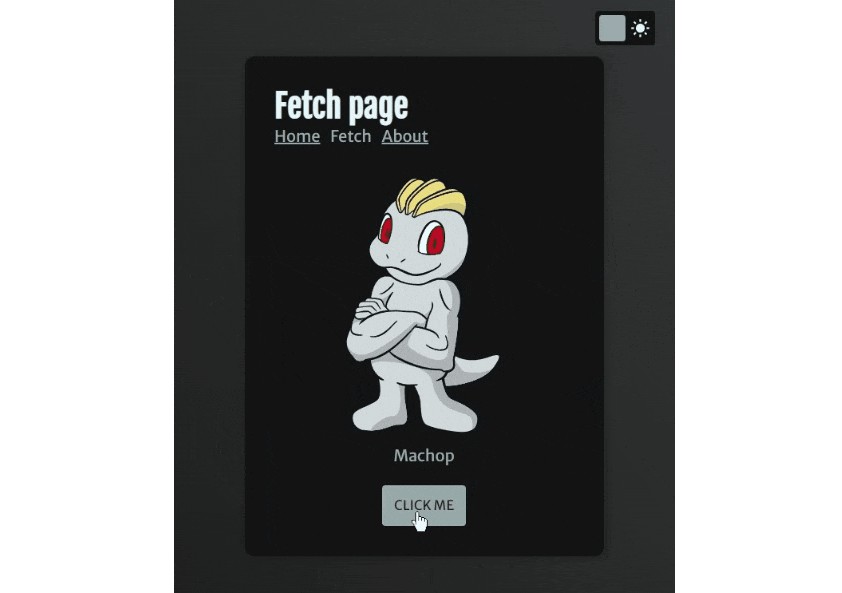

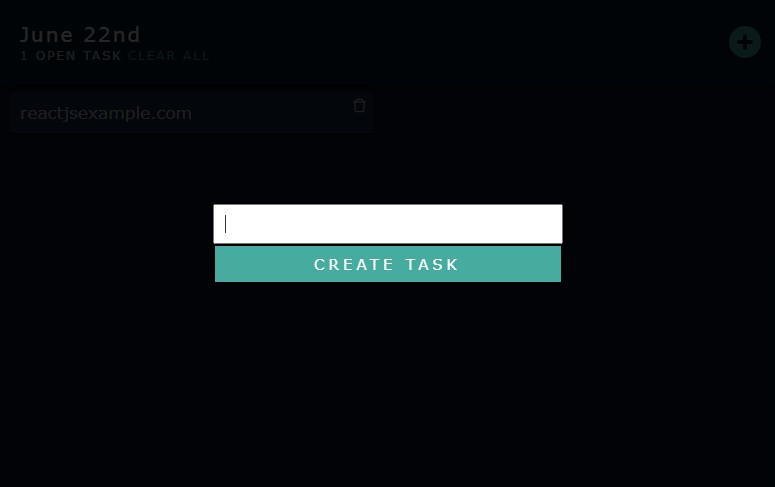

This project is a starting point for a TypeScript based React app that also has a local API server using Express. It serves as an excellent “sandbox” for learning the workflow of a full stack web application from our Bootcamp. There is no connection to any kind of database, but our videos and course cover MySQL and its integration into Node and Express.

Keep in mind there isn’t much quality of life in this Boilerplate code, you’ll miss your “hot reloading” feature of Create React App, the ability to import pictures as modules, and all the other fun stuff the big frameworks have already coded for you. They’re all still accessible, but you’d have to learn to add them yourself! Feel free to ping me (@Cool Hand Luke) in our Discord channel if you’re a student and are interested in a particular feature you’d like to see a tutorial on. ?

? Running the Project

If you already know the process of cloning a repository then follow the normal process and use the script npm run dev to get up and going!

If you’re new or are interested in the steps and their purpose, then let’s dive on in!

First:

git clone https://github.com/covalence-io/barebones-react-typescript-express.git YOUR_PROJECT_NAME

This command will “clone” this project’s code to our computers! It will default to the name of the GitHub repository, but you can rename it by providing an additional argument, like YOUR_PROJECT_NAME in the above example. It will create a folder by that name, and copy all the juicy code into it for you!

Second:

cd YOUR_PROJECT_NAME

Hopefully this one is fairly straightforward by this point ?. It will change directories into the folder we just cloned the code into. Note, there are some cool shorthands you could do to combine some of these steps or making a function/alias to streamline it!

Third:

npm install

This is also hopefully straightforward by now ?: it will look into the package.json and package-lock.json to install the needed dependencies for this project to do its job. It will create your node_modules folder for you which is what makes time travel possible lets the project run.

- Note that sometimes you’ll see security vulnerabilities. These will come and go and thankfully are easy to fix.

npm audit fixcan do so by updating an out-of-date package to a new version. However, alot of these free packages are written in the spare time of other developers and you’re at the mercy of waiting for them to fix the vulnerability.

Fourth:

npm run dev

This command will start the project for us! It will sometimes take a bit, depending on the speed of the computer, anywhere from 10 to 20 seconds feels average. Don’t stress if your old junker of a laptop takes longer! As long as it completes without error you’re good to go. ?

- This script will utilize

nodemonto auto-restart your Express server, meaning any server side code you write and save will trigger a recompile, rebundle, and re-run of the server! No need to stop and restart it over and over again. - Notice in the

package.jsonthatdevruns"npm-run-all --parallel watch:*"as the actual command. It’s what fires up 1)webpackto compile and bundle our code and 2) runnodemonwhen the server finishes building!- The

npm-run-alllets us run run multiple npm-scripts in parallel or sequentialy. --parallelmeans we run two npm-scripts at the same time.watch:*references any other script starting withwatch:, check out the two in ourpackage.json! They arewatch:buildandwatch:server.- Another indent level? ? Sheesh. But let’s break down the purpose of those watch scripts!

watch:buildwill tell webpack to compile and bundle oursrc/clientfolder as all of our React app and output it topublic/js/app.js. It will also follow the same process forsrc/serverand output it todist/server.jswatch:serverwatches thedist/server.jsfor changes and that’s how it auto-restarts the server! Unfortunately you’ll have to refresh your browser to see any React app changes.

- The

The server will start on port 3000 (http://localhost:3000) and should default to a “Hello World” app!

Optionally:

npm run start

We will use this script in production. We don’t need all the auto-restart stuff from the watch:* scripts we discussed up above. Just start the server and be done with it.

- This assumes you have a

dist/server.jsandpublic/js/app.jsalready built.

? Server

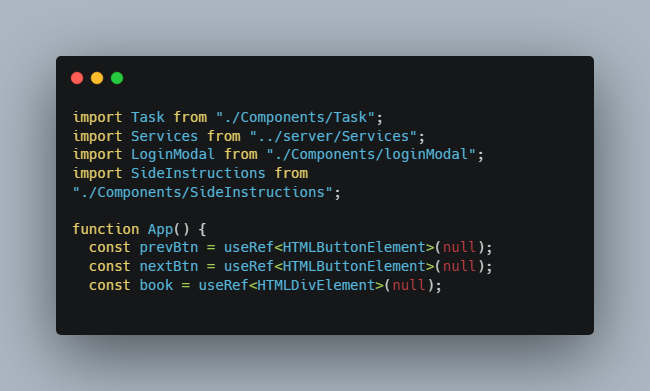

The server build process compiles the TypeScript files found in src/server into a single bundled JavaScript file (server.js) located in the dist directory, which is created for us during the process.

This will be where we code all things relating to our database, whether SQL or NoSQL. It’s where we’ll include all of our REST API routes. All of our back-end utilities. While there are tricks to share its code, we will not be sharing any code from our src/server folder into src/client. If you find yourself wanting to import anything directly to your client code from your server code. ✋ Stop ✋ and rethink how you’re trying to solve this problem. For all intents and purposes back-end and front-end are entirely separate realms of existence.

? Client

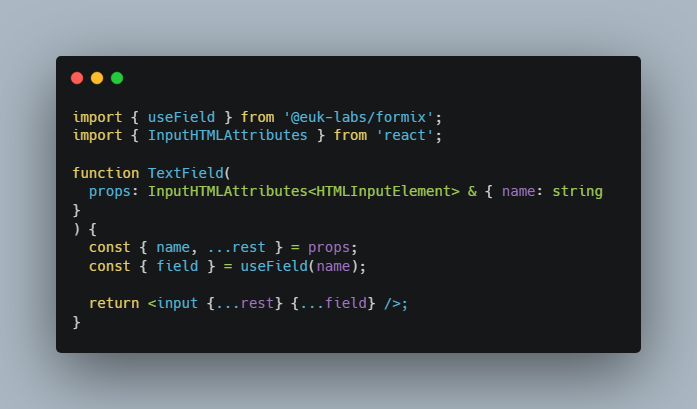

The client build process compiles the TypeScript files found in src/client into a single bundled JavaScript file (app.js) located in the public/js/ directory, which is created for us during the process.

This will be where we code all things related to our React app and what a user will see and interact with in the browser. That’s it. If it needs to ask for any information on the back-end, you will 99% of the time do so via a fetch request that hits one of your REST API endpoints.

? Styling the App

The src/client configuration will also build the SASS files found at src/client/scss directory. The index.tsx imports the app.scss file which already includes an import for Bootstrap v4. Notice how the Bootstrap import in the src/client/scss/app.scss file is at the bottom of the file. This is because our expected overrides are expected above that import. Think of it as “here’s my custom Bootstrap injections ? .. and now load Bootstrap with my changes, mwahaha!”

Thankfully, you can write normal CSS just as you like! Add class selectors, element selecotrs, and id selectors to your hearts ? content. There are, however, several SASS tricks you can research on Google, Stack Overflow, Youtube, and etc. Covalence thanks to Matt Landers has two entry-level videos discussing SASS and its advantages over regular CSS:

- Let’s Get Sassy which is an intro to SASS as a concept, its advantages over regular CSS, how to add it to a project (remember you don’t need to do that here), and some tricks to using it.

- Overriding Bootstrap Variables which goes over the basics of … overriding Bootstrap variables! You’ll notice this boilerplate already provides a basic example of that:

// First override some or all individual color variables

$primary: #25408f;

$secondary: #8f5325;

$success: #3e8d63;

$info: #13101c;

$warning: #945707;

$danger: #d62518;

$light: #f8f9fa;

$dark: #343a40;

// Then add them to your custom theme-colors map, together with any additional colors you might need

$theme-colors: (

primary: $primary,

secondary: $secondary,

success: $success,

info: $info,

warning: $warning,

danger: $danger,

light: $light,

dark: $dark,

// add any additional color below

);

This takes the all Bootstrap variables anywhere you use it and replaces it with a new color code! Add bg-primary, text-primary, and border-primary to some elements in your TSX and notice how the regular deep blue Bootstrap color is now replaced by our custom one. You can override all the color-specific keywords using this to add your own custom feel to your React Bootstrap app!

?️ Configuration Files

-

.gitignoreis what we use to not push certain files or folders to GitHub. This starts with our dependencies and production bundles being ignored. Feel free to add any file that contains sensitive information away from GitHub using this. A common addition would be a.envfile, for example, that contains our 3rd Party API Keys. -

package-lock.jsonis automatically generated whenever you run a command that modifiesnode_modulesorpackage.json. It describes the exact modification that was made, such that subsequent installs (like you cloning this boilerplate and installing modules! ?) are able to generate identical modifications, regardless of intermediate dependency updates. -

package.jsonyou’ve seen this one a lot, it’s the basic “metadata” relevant to the project and it is used for managing the project’s dependencies, scripts, version and a whole lot more. -

README.mdthe markdown file that displays here in GitHub that you’re reading right now. And what I probably use as my “lecture” notes during my videos! -

tsconfig.client.jsonthe TypeScript rules our TSC compiler will follow and allow when building our React app. There are several options to play with to standarizeimportstatements, allow the use ofany(don’t do this though lol), but make sure not to remove"jsx": "react",by mistake or it won’t know what you’re trying to write in those.tsxfiles! -

tsconfig.server.jsonthe same as above, basically, except for our server code. We tell it to include the types fornodeandexpressso it can help us write the basics of our server with improved intellisense support and less manual strong typing. Basically it makes our TSC “infer” some of the basic server types for us automatically. -

webpack.config.jsthe rules, loaders, and plugins our entire build process follows. There’s a lot of stuff bundled ?? in this one .. so let’s break down the high points in its own subsection below.

⁉️ Webpack Config ??

When I was but a young dev student, I once attended a local meetup about React when it was still fairly new. The speaker was a very experienced dev who was leading our “lunch and learn” discussion. My favorite quote he lead with is forever forged into my memories. “I spent the last week trying to learn more about Webpack so I can talk about it up here today and teach you all. I feel like I know less than when I started.”

That sums up my own thoughts better than my own words could. That being said, here’s what you’re staring at, and we’re gonna literally go top down on this sucker:

const nodeExternals = require('webpack-node-externals');

When bundling with Webpack for the backend – you usually don’t want to bundle its node_modules dependencies. This library creates an externals function that ignores node_modules when bundling in Webpack. So this is used as a “plugin” in the config here: externals: [nodeExternals()] in the serverConfig object. Basically it’s making sure we’re not trying to build external stuff by accident that doesn’t need to be.

const serverConfig = { ... }

This is the object we create for the compile and bundle process for our src/server code.

mode: process.env.NODE_ENV || 'development',

This tells Webpack whether it’s in development or some other mode, typically production. Are we goofing around on our local machines tinkering with a new feature and we want verbose error messages that trace back in source code where the problem occured? Or are we debugging a problem after we deploy our site and wonder why it crashed after we let our friend touch it? Webpack will have different types of outputs depending on this. Note that it defaults to development unless we set NODE_ENV as an environment variable to production. This is typically set for us on Heroku by default.

module: { ... },

resolve: { ... },

output: { ... },

target: 'node',

Don’t stress about the guts of these properties, just focus on their general purpose.

modulelets us specify what to do with certain file extensions. If Webpack encounters a.tsextension, we provide rules, loaders, and options for it to do certain tasks when building them.resolvethis deals with how modules are “resolved.” As in if we writeimport 'lodash'in ES2015, the resolve options can change where webpack goes to look for ‘lodash’ for us. You probably won’t mess with this much.outputis where we output our bundle to, which isdist/server.js.targetbecause JavaScript can be written for both server and browser, webpack offers multiple deployment targets that you can set in your configuration. This is the server object, so we make sure to tell Webpack we’re using server JavaScript code.

const clientConfig = { ... }

This is the object we create for the compile and bundle process for our src/client code.

mode: process.env.NODE_ENV || 'development',

This tells Webpack whether it’s in development or some other mode, typically production. Are we goofing around on our local machines tinkering with a new feature and we want verbose error messages that trace back in source code where the problem occured? Or are we debugging a problem after we deploy our site and wonder why it crashed after we let our friend touch it? Webpack will have different types of outputs depending on this. Note that it defaults to development unless we set NODE_ENV as an environment variable to production. This is typically set for us on Heroku by default.

devtool: 'inline-source-map',

This attempts to help you when developing your React app. Remember we’re going through several “layers” before running our code in the browser. TypeScript React down to JavaScript React down to JavaScript DOM using React.createElement(); and into the browser. That’s a bunch of steps in between what you write and what you see running! This attempts to map back to your original source code what error or what is running the browser.

module: { ... },

resolve: { ... },

output: { ... },

Don’t stress about the guts of these properties, just focus on their general purpose.

modulelets us specify what to do with certain file extensions. If Webpack encounters a.tsextension, we provide rules, loaders, and options for it to do certain tasks when building them.resolvethis deals with how modules are “resolved.” As in if we writeimport 'lodash'in ES2015, the resolve options can change where webpack goes to look for ‘lodash’ for us. You probably won’t mess with this much.outputis where we output our bundle to, which ispublic/js/app.js.

? Closing Remarks

There are a lot of moving parts even in this barebones boilerplate! This is why we provide it to you, the student, as a jumping off point. We want you to focus on coding your server code and React code. Not mess with configuration files and project setup. Keep in mind this is not the be-all-end-all boilerplate. You can learn what features you miss from things like NextJS, GatsbyJS, and Create React App and figure out how to add them to this one to make it your go-to starter.

Code, code, and code. Build shit and deploy. Get projects up and running, conceptually finished, and no matter how dumb. You will always learn something new. Challenge yourself to use different CSS Kits and libraries. Try other database connectors. Try React libraries like Redux. Even if you aren’t getting paid for it, it’s still valuable experience for you. So happy hacking, and have some fun!