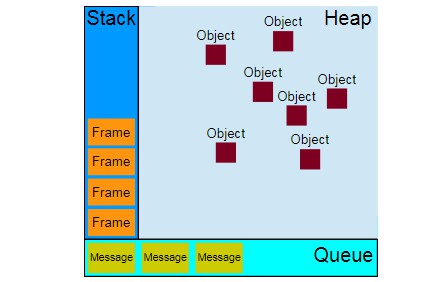

javascript working principle (event loop, call stack, queue)

Concurrency model and the event loop

JavaScript has a concurrency model based on an event loop, which is responsible for executing the code, collecting and processing events, and executing queued sub-tasks. This model is quite different from models in other languages like C and Java.

Runtime concepts

The following sections explain a theoretical model. Modern JavaScript engines implement and heavily optimize the described semantics.

Visual representation

Stack

Function calls form a stack of frames.

function foo(b) {

let a = 10

return a + b + 11

}

function bar(x) {

let y = 3

return foo(x * y)

}

const baz = bar(7) // assigns 42 to baz

Copy to Clipboard

Order of operations:

- When calling

bar, a first frame is created containing references tobar‘s arguments and local variables. - When

barcallsfoo, a second frame is created and pushed on top of the first one, containing references tofoo‘s arguments and local variables. - When

fooreturns, the top frame element is popped out of the stack (leaving onlybar‘s call frame). - When

barreturns, the stack is empty.

Note that the arguments and local variables may continue to exist, as they are stored outside the stack — so they can be accessed by any nested functions long after their outer function has returned.

Heap

Objects are allocated in a heap which is just a name to denote a large (mostly unstructured) region of memory.

Queue

A JavaScript runtime uses a message queue, which is a list of messages to be processed. Each message has an associated function that gets called to handle the message.

At some point during the event loop, the runtime starts handling the messages on the queue, starting with the oldest one. To do so, the message is removed from the queue and its corresponding function is called with the message as an input parameter. As always, calling a function creates a new stack frame for that function’s use.

The processing of functions continues until the stack is once again empty. Then, the event loop will process the next message in the queue (if there is one).

Event loop

The event loop got its name because of how it’s usually implemented, which usually resembles:

while (queue.waitForMessage()) {

queue.processNextMessage()

}

Copy to Clipboard

queue.waitForMessage() waits synchronously for a message to arrive (if one is not already available and waiting to be handled).

Run-to-completion

Each message is processed completely before any other message is processed.

This offers some nice properties when reasoning about your program, including the fact that whenever a function runs, it cannot be pre-empted and will run entirely before any other code runs (and can modify data the function manipulates). This differs from C, for instance, where if a function runs in a thread, it may be stopped at any point by the runtime system to run some other code in another thread.

A downside of this model is that if a message takes too long to complete, the web application is unable to process user interactions like click or scroll. The browser mitigates this with the “a script is taking too long to run” dialog. A good practice to follow is to make message processing short and if possible cut down one message into several messages.

Adding messages

In web browsers, messages are added anytime an event occurs and there is an event listener attached to it. If there is no listener, the event is lost. So a click on an element with a click event handler will add a message—likewise with any other event.

The function setTimeout is called with 2 arguments: a message to add to the queue, and a time value (optional; defaults to 0). The time value represents the (minimum) delay after which the message will be pushed into the queue. If there is no other message in the queue, and the stack is empty, the message is processed right after the delay. However, if there are messages, the setTimeout message will have to wait for other messages to be processed. For this reason, the second argument indicates a minimum time—not a guaranteed time.

Here is an example that demonstrates this concept (setTimeout does not run immediately after its timer expires):

const seconds = new Date().getSeconds();

setTimeout(function() {

// prints out "2", meaning that the callback is not called immediately after 500 milliseconds.

console.log(`Ran after ${new Date().getSeconds() - seconds} seconds`);

}, 500)

while (true) {

if (new Date().getSeconds() - seconds >= 2) {

console.log("Good, looped for 2 seconds")

break;

}

}

Copy to Clipboard

Zero delays

Zero delay doesn’t mean the call back will fire-off after zero milliseconds. Calling setTimeout with a delay of 0 (zero) milliseconds doesn’t execute the callback function after the given interval.

The execution depends on the number of waiting tasks in the queue. In the example below, the message "this is just a message" will be written to the console before the message in the callback gets processed, because the delay is the minimum time required for the runtime to process the request (not a guaranteed time).

The setTimeout needs to wait for all the code for queued messages to complete even though you specified a particular time limit for your setTimeout.

(function() {

console.log('this is the start');

setTimeout(function cb() {

console.log('Callback 1: this is a msg from call back');

}); // has a default time value of 0

console.log('this is just a message');

setTimeout(function cb1() {

console.log('Callback 2: this is a msg from call back');

}, 0);

console.log('this is the end');

})();

// "this is the start"

// "this is just a message"

// "this is the end"

// "Callback 1: this is a msg from call back"

// "Callback 2: this is a msg from call back"

Copy to Clipboard

Several runtimes communicating together

A web worker or a cross-origin iframe has its own stack, heap, and message queue. Two distinct runtimes can only communicate through sending messages via the postMessage method. This method adds a message to the other runtime if the latter listens to message events.

Never blocking

A very interesting property of the event loop model is that JavaScript, unlike a lot of other languages, never blocks. Handling I/O is typically performed via events and callbacks, so when the application is waiting for an IndexedDB query to return or an XHR request to return, it can still process other things like user input.

Legacy exceptions exist like alert or synchronous XHR, but it is considered good practice to avoid them. Beware: exceptions to the exception do exist (but are usually implementation bugs, rather than anything else).

See also

Call stack

A call stack is a mechanism for an interpreter (like the JavaScript interpreter in a web browser) to keep track of its place in a script that calls multiple functions — what function is currently being run and what functions are called from within that function, etc.

- When a script calls a function, the interpreter adds it to the call stack and then starts carrying out the function.

- Any functions that are called by that function are added to the call stack further up, and run where their calls are reached.

- When the current function is finished, the interpreter takes it off the stack and resumes execution where it left off in the last code listing.

- If the stack takes up more space than it had assigned to it, it results in a “stack overflow” error.

Example

function greeting() {

// [1] Some code here

sayHi();

// [2] Some code here

}

function sayHi() {

return "Hi!";

}

// Invoke the `greeting` function

greeting();

// [3] Some code here

Copy to Clipboard

The code above would be executed like this:

-

Ignore all functions, until it reaches the

greeting()function invocation. -

Add the

greeting()function to the call stack list.Note: Call stack list: – greeting

-

Execute all lines of code inside the

greeting()function. -

Get to the

sayHi()function invocation. -

Add the

sayHi()function to the call stack list.Note: Call stack list: – sayHi – greeting

-

Execute all lines of code inside the

sayHi()function, until reaches its end. -

Return execution to the line that invoked

sayHi()and continue executing the rest of thegreeting()function. -

Delete the

sayHi()function from our call stack list.Note: Call stack list: – greeting

-

When everything inside the

greeting()function has been executed, return to its invoking line to continue executing the rest of the JS code. -

Delete the

greeting()function from the call stack list.

**Note:** Call stack list: EMPTY

In summary, then, we start with an empty Call Stack. Whenever we invoke a function, it is automatically added to the Call Stack. Once the function has executed all of its code, it is automatically removed from the Call Stack. Ultimately, the Stack is empty again.

See also

- Call stack on Wikipedia

- Glossary

Using microtasks in JavaScript with queueMicrotask()

A microtask is a short function which is executed after the function or program which created it exits and only if the JavaScript execution stack is empty, but before returning control to the event loop being used by the user agent to drive the script’s execution environment.

This event loop may be either the browser’s main event loop or the event loop driving a web worker. This lets the given function run without the risk of interfering with another script’s execution, yet also ensures that the microtask runs before the user agent has the opportunity to react to actions taken by the microtask.

JavaScript promises and the Mutation Observer API both use the microtask queue to run their callbacks, but there are other times when the ability to defer work until the current event loop pass is wrapping up. In order to allow microtasks to be used by third-party libraries, frameworks, and polyfills, the queueMicrotask() method is exposed on the Window and Worker interfaces.

Tasks vs microtasks

To properly discuss microtasks, it’s first useful to know what a JavaScript task is and how microtasks differ from tasks. This is a quick, simplified explanation, but if you would like more details, you can read the information in the article In depth: Microtasks and the JavaScript runtime environment.

Tasks

A task is any JavaScript code which is scheduled to be run by the standard mechanisms such as initially starting to run a program, an event callback being run, or an interval or timeout being fired. These all get scheduled on the task queue.

Tasks get added to the task queue when:

- A new JavaScript program or subprogram is executed (such as from a console, or by running the code in a

<script>element) directly. - An event fires, adding the event’s callback function to the task queue.

- A timeout or interval created with

setTimeout()orsetInterval()is reached, causing the corresponding callback to be added to the task queue.

The event loop driving your code handles these tasks one after another, in the order in which they were enqueued. Only tasks which were already in the task queue when the event loop pass began will be executed during the current iteration. The rest will have to wait until the following iteration.

Microtasks

At first the difference between microtasks and tasks seems minor. And they are similar; both are made up of JavaScript code which gets placed on a queue and run at an appropriate time. However, whereas the event loop runs only the tasks present on the queue when the iteration began, one after another, it handles the microtask queue very differently.

There are two key differences.

First, each time a task exits, the event loop checks to see if the task is returning control to other JavaScript code. If not, it runs all of the microtasks in the microtask queue. The microtask queue is, then, processed multiple times per iteration of the event loop, including after handling events and other callbacks.

Second, if a microtask adds more microtasks to the queue by calling queueMicrotask(), those newly-added microtasks execute before the next task is run. That’s because the event loop will keep calling microtasks until there are none left in the queue, even if more keep getting added.

Warning: Since microtasks can themselves enqueue more microtasks, and the event loop continues processing microtasks until the queue is empty, there’s a real risk of getting the event loop endlessly processing microtasks. Be cautious with how you go about recursively adding microtasks.

Using microtasks

Before getting farther into this, it’s important to note again that most developers won’t use microtasks much, if at all. They’re a highly specialized feature of modern browser-based JavaScript development, allowing you to schedule code to jump in front of other things in the long set of things waiting to happen on the user’s computer. Abusing this capability will lead to performance problems.

Enqueueing microtasks

As such, you should typically use microtasks only when there’s no other solution, or when creating frameworks or libraries that need to use microtasks in order to create the functionality they’re implementing. While there have been tricks available that made it possible to enqueue microtasks in the past (such as by creating a promise that resolves immediately), the addition of the queueMicrotask() method adds a standard way to introduce a microtask safely and without tricks.

By introducing queueMicrotask(), the quirks that arise when sneaking in using promises to create microtasks can be avoided. For instance, when using promises to create microtasks, exceptions thrown by the callback are reported as rejected promises rather than being reported as standard exceptions. Also, creating and destroying promises takes additional overhead both in terms of time and memory that a function which properly enqueues microtasks avoids.

Pass the JavaScript Function to call while the context is handling microtasks into the queueMicrotask() method, which is exposed on the global context as defined by either the Window or Worker interface, depending on the current execution context.

queueMicrotask(() => {

/* code to run in the microtask here */

});

Copy to Clipboard

The microtask function itself takes no parameters, and does not return a value.

When to use microtasks

In this section, we’ll take a look at scenarios in which microtasks are particularly useful. Generally, it’s about capturing or checking results, or performing cleanup, after the main body of a JavaScript execution context exits, but before any event handlers, timeouts and intervals, or other callbacks are processed.

When is that useful?

The main reason to use microtasks is that: to ensure consistent ordering of tasks, even when results or data is available synchronously, but while simultaneously reducing the risk of user-discernible delays in operations.

Ensuring ordering on conditional use of promises

One situation in which microtasks can be used to ensure that the ordering of execution is always consistent is when promises are used in one clause of an if...else statement (or other conditional statement), but not in the other clause. Consider code such as this:

customElement.prototype.getData = url => {

if (this.cache[url]) {

this.data = this.cache[url];

this.dispatchEvent(new Event("load"));

} else {

fetch(url).then(result => result.arrayBuffer()).then(data => {

this.cache[url] = data;

this.data = data;

this.dispatchEvent(new Event("load"));

});

}

};

Copy to Clipboard

The problem introduced here is that by using a task in one branch of the if...else statement (in the case in which the image is available in the cache) but having promises involved in the else clause, we have a situation in which the order of operations can vary; for example, as seen below.

element.addEventListener("load", () => console.log("Loaded data"));

console.log("Fetching data...");

element.getData();

console.log("Data fetched");

Copy to Clipboard

Executing this code twice in a row gives the following results.

When the data is not cached:

Fetching data

Data fetched

Loaded data

When the data is cached:

Fetching data

Loaded data

Data fetched

Even worse, sometimes the element’s data property will be set and other times it won’t be by the time this code finishes running.

We can ensure consistent ordering of these operations by using a microtask in the if clause to balance the two clauses:

customElement.prototype.getData = url => {

if (this.cache[url]) {

queueMicrotask(() => {

this.data = this.cache[url];

this.dispatchEvent(new Event("load"));

});

} else {

fetch(url).then(result => result.arrayBuffer()).then(data => {

this.cache[url] = data;

this.data = data;

this.dispatchEvent(new Event("load"));

});

}

};

Copy to Clipboard

This balances the clauses by having both situations handle the setting of data and firing of the load event within a microtask (using queueMicrotask() in the if clause and using the promises used by fetch() in the else clause).

Batching operations

You can also use microtasks to collect multiple requests from various sources into a single batch, avoiding the possible overhead involved with multiple calls to handle the same kind of work.

The snippet below creates a function that batches multiple messages into an array, using a microtask to send them as a single object when the context exits.

const messageQueue = [];

let sendMessage = message => {

messageQueue.push(message);

if (messageQueue.length === 1) {

queueMicrotask(() => {

const json = JSON.stringify(messageQueue);

messageQueue.length = 0;

fetch("url-of-receiver", json);

});

}

};

Copy to Clipboard

When sendMessage() gets called, the specified message is first pushed onto the message queue array. Then things get interesting.

If the message we just added to the array is the first one, we enqueue a microtask that will send a batch. The microtask will execute, as always, when the JavaScript execution path reaches the top level, just before running callbacks. That means that any further calls to sendMessage() made in the interim will push their messages onto the message queue, but because of the array length check before adding a microtask, no new microtask is enqueued.

When the microtask runs, then, it has an array of potentially many messages waiting for it. It starts by encoding it as JSON using the JSON.stringify() method. After that, the array’s contents aren’t needed anymore, so we empty the messageQueue array. Finally, we use the fetch() method to send the JSON string to the server.

This lets every call to sendMessage() made during the same iteration of the event loop add their messages to the same fetch() operation, without potentially having other tasks such as timeouts or the like delay the transmission.

The server will receive the JSON string, then will presumably decode it and process the messages it finds in the resulting array.

Examples

Simple microtask example

In this simple example, we see that enqueueing a microtask causes the microtask’s callback to run after the body of this top-level script is done running.

JavaScript

In the following code, we see a call to queueMicrotask() used to schedule a microtask to run. This call is bracketed by calls to log(), a custom function that outputs text to the screen.

log("Before enqueueing the microtask");

queueMicrotask(() => {

log("The microtask has run.")

});

log("After enqueueing the microtask");

Copy to Clipboard

Result

Timeout and microtask example

In this example, a timeout is scheduled to fire after zero milliseconds (or “as soon as possible”). This demonstrates the difference between what “as soon as possible” means when scheduling a new task (such as by using setTimeout()) versus using a microtask.

JavaScript

In the following code, we see a call to queueMicrotask() used to schedule a microtask to run. This call is bracketed by calls to log(), a custom function that outputs text to the screen.

The code below schedules a timeout to occur in zero milliseconds, then enqueues a microtask. This is bracketed by calls to log() to output additional messages.

let callback = () => log("Regular timeout callback has run");

let urgentCallback = () => log("*** Oh noes! An urgent callback has run!");

log("Main program started");

setTimeout(callback, 0);

queueMicrotask(urgentCallback);

log("Main program exiting");

Copy to Clipboard

Result

Note that the output logged from the main program body appears first, followed by the output from the microtask, followed by the timeout’s callback. That’s because when the task that’s handling the execution of the main program exits, the microtask queue gets processed before the task queue on which the timeout callback is located. Remembering that tasks and microtasks are kept on separate queues, and that microtasks run first will help keep this straight.

Microtask from a function

This example expands slightly on the previous one by adding a function that does some work. This function uses queueMicrotask() to schedule a microtask. The important thing to take away from this one is that the microtask isn’t processed when the function exits, but when the main program exits.

JavaScript

The main program code follows. The doWork() function here calls queueMicrotask(), yet the microtask still doesn’t fire until the entire program exits, since that’s when the task exits and there’s nothing else on the execution stack.

let callback = () => log("Regular timeout callback has run");

let urgentCallback = () => log("*** Oh noes! An urgent callback has run!");

let doWork = () => {

let result = 1;

queueMicrotask(urgentCallback);

for (let i=2; i<=10; i++) {

result *= i;

}

return result;

};

log("Main program started");

setTimeout(callback, 0);

log(`10! equals ${doWork()}`);

log("Main program exiting");

log("Regular timeout callback has run");

Copy to Clipboard